Fundamentally there was no housing bubble?-Update

Lance on Feb 14 2008 at 12:19 pm | Filed under: Economics, Lance's Page, Urban planning and development, regulation

So claims Alex Tabarrok. Alex and his blogmate Tyler are two of my favorite bloggers, but on this matter I think Alex is wrong. Unlike for some, his argument doesn’t invite scorn from me, because humility should teach us that sometimes things are different, and we cannot always fully understand why, at least not until after the fact. Later people laugh at we fools for missing the obvious. It always seems obvious after the fact. A belief in uncertainty is a virtue in understanding markets, and history. That being said, I still think Alex is wrong.

The crux of his argument is this:

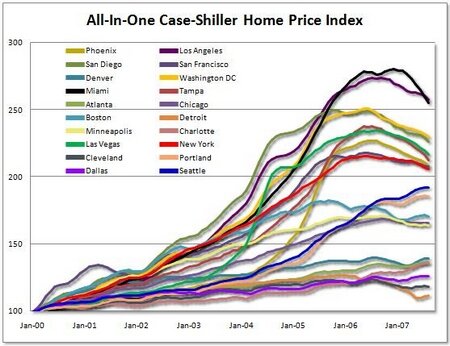

So if the massive run-up in house prices since 1997 was a bubble and if the bubble has now been popped we should see a massive drop in prices. But what has actually happened? House prices have certainly stopped increasing and they have dropped but they have not dropped to anywhere near the historic average (see chart in the extension). Since the peak in the second quarter of 2006 prices have dropped by about 5% at the national level (third quarter 2007).

Except the argument has never been that prices would decrease immediately or quickly. The consensus of those of us who have worried about this has been that it would be a transition which would take years. Housing doesn’t correct quickly as a rule.

Alex feels the market has shifted to a new higher equilibrium:

If we don’t see the massive drop back to “normal” levels then the run up in prices should be described as a shift to a new equilibrium - much as happened during World War II - see the chart. (It’s an important question to ask what changed and why?). In the shift to the new equilibrium there was some mild overshooting, especially due to the subprime over expansion, but fundamentally there was no housing bubble.

I actually agree that in some markets we may see a new higher equilibrium, say California, but it will take a large drop first. Here is the chart showing price declines from above, but updated to reflect recent declines (Alex’s chart is old)

Frankly, those are some pretty scary declines, and now they are across the board, not just the hottest markets. This chart isn’t adjusted for inflation however, so the declines are happening in close to real terms, while the increase is merely nominal, making the increase seem more dramatic and the declines less so than they are.

In my mind real prices (that is prices adjusted for inflation) will fall at least another 25% on average, with nominal prices not seeming to fall as much, as inflation over the next few years eats into it. I suspect we will see a great deal of this fall come from stagnating nominal prices with inflation catching people up. I hope so at least. Too rapid a fall would make it more difficult for people, and the financial markets, to digest.

What about that new equilibrium? Megan McCardle discusses this issue:

What bothers me is that I don’t understand why we should have shifted to a new equilibrium. I think I understand the reasons that the equilibrium values shifted between 1940 and 1950:

- Developments in rail and construction techniques in the 1910-20 brought huge amounts of land under development, and pushed urban buildings rapidly upward, at a time when population growth was slowing, depressing prices

- The Great Depression kept them low

- This massive pent up demand translated into a boom in housing demands as incomes recovered

- The FHA, and then the Veterans administration, basically introduced an entirely new product: the long term amortizing mortgage. Previously, mortgages had been short-term affairs with balloon payments at the end; five years was a very standard term. The long-term amortizing mortgage, especially when helped along with government subsidies, massively increased the amount a couple could pay for their house.

- Housing demand was then sustained by high rates of real economic growth and population growth, which caused housing demand to skyrocket.

- Prices leveled off as the automobile brought new land into housing, but since the mortgages kept demand pegged to incomes, they never actually fell

- The post-1970 fluctuations are money illusion, responses to changes in nominal interest rates.

I find it hard to name a comparable equilibrium changing development in 1997.

The reason I am willing to think that it may happen to some extent is that in looking at the first chart one notices that markets with constrained available housing supply rose the fastest. Most of these cities have restricted the ability of the market to supply housing. Absent those restrictions the increases would have likely been more along the lines of Dallas and other cities which have the lowest rise. Megan makes that her one caveat as well:

I am fairly well convinced Ed Glaeser’s argument that high coastal real estate prices are due at least in part to the fact that local interests are increasingly effective at blocking new development. But that’s been going on for decades; it didn’t suddenly change in 1997.

Given that the largest increases occurred in just the kind of areas where Glaser says they should, it does give Tyler’s view credence. While I am willing to entertain the possibility, I find it very questionable. It is instead to me more likely to be one of the driving forces behind the bubble, not an explanation for why there wasn’t one.

While Shiller’s charts show the kind of rise which should give us all pause, they don’t actually get at the heart of the matter, which is affordability. Housing has to be affordable. If one looks at the cost of owning a home versus income, the rates are really scary, especially in the markets we look at above. While a lack of land or other restrictions can increase the cost of housing in the short run, and certainly were part of the story here (that is simple supply and demand) long term it likely doesn’t matter, and I suspect it will not establish a much higher equilibrium even in those types of markets.

Why? Because people can move. The US has abundant land, even around its major cities. We have only urbanized (including suburbs and exurbs) only about 3% of our land mass. People were willing to pay above average amounts for housing in places where housing has been restricted because they felt they were profiting from the rise. People will probably not go on paying 5 to 10 times income if they stop believing that appreciation will bail them out. The housing bubble gained momentum in these areas because of the restrictions, then speculation drove the price far beyond what could reasonably be carried. Now that process is in reverse. The likely outcome is that housing will go back to being a fairly tight band around 3-4 times local income on a national basis. This arbitrage between high housing cost and lower housing cost areas will slowly work that excess out. Possibly over decades.

Some have claimed that lower cost mortgages that people took out in the past will allow them to permanently keep a higher value on their home. That doesn’t work. The housing markets prices are set at the margin. It is buyers and sellers of homes who set the prices, not people who have homes that due to past low interest rates can afford to stay in their existing homes. New mortgages are the issue, not those already in place. Besides, housing prices in many of these areas were already unaffordable before the dramatic drop in interest rates. Without the promise of appreciation and the equity gains they led to, they are no longer affordable regardless of when they took out their mortgage. To afford the home, many took out home equity loans to live. Now they do not have that option.

Worse, we could see over shooting to the down side. The credit debacle (which extends far past subprime, one of the key errors has been seeing it as just a subprime, or even housing, issue) could make this unravel faster than I expect and lead to areas which did not participate in the bubble suffering right along with everybody else. The declines due to a reversal of speculation could therefore lead to even lower prices.

I would say there is a bright spot to all this. Housing needs to be more affordable. The adjustment will be painful, but in the long run prices, especially on a key consumption good such as a home, would serve us better not to go up faster than inflation. I have long been arguing that governments who restrict housing and make it less affordable should not be bragging about rising property values. Not only is it a hardship for most people, but it makes the housing market more volatile, as this year is making clear. It is not because they have made their communities more attractive. It is decreased supply, not increased demand, that is the primary driver of the increase.

In our firm we have been harping on this long before it started to show itself. It is going at about the pace we expected, if not a bit faster. So Alex, as often as we agree, I have to part ways with you on this one. We have a bubble.

Update: Keith sent me this link on new research out of Seattle showing the impact of housing regulations on the cost of housing there.

Sphere: Related Content8 Responses to “Fundamentally there was no housing bubble?-Update”

Trackback URI | Comments RSS

So if I was looking to buy a house, when would be a good time? Though living in houston, I don’t think the market here has been affected that much.

Houston didn’t run up as much. The thing to remember is it should be a home, not an investment. You can’t know the future, but anything which assumes gains should be avoided. Make sure you can afford it, and that if it goes down in price you have no problem staying in it until it doesn’t lose money. Housing is a bad investment, but a great purchase, except in rare circumstances. We just lived through one of those, but generally housing tracks just above inflation.

In fact, if you work out the numbers, renting is a better deal from an economic sense on the whole. Except, if you live in it a very long time. Why? Because if you don’t take the equity out and drive up the payments, your rent, which you are paying as mortgage, has been set for 30 years. Needless to say, your mortgage payment will seem rather small in a decade or two.

I plan on doing a post on the economics of owning a house, as most I have seen do not teat the issue thoroughly and thus mislead people by ignoring key aspects.

Housing is really a consumption good. You buy because you want to own a house, not because it makes you better off. If that happens it is all gravy.

cool. I’m young and single, with a steady income. I just bought a truck 4 months ago, a hd tv 2 years before that, so I figured a house is what I should be saving up for next. I’d be interested in the contrasts between purchasing a house vs a condo/town home type thing. I’m really just looking for some place to own and live in for the foreseeable future.

Lance, your points are good ones. I’m sure your analysis will include things like maintenance and sales commissions, which do complicate the situation and can make a superficial rent-to-payment comparison invalid.

But don’t forget the intangibles of owning a house in your analysis. We freedom-oriented types really like the fact that we can do whatever the heck we want to our domiciles. My back yard is a go-cart track until my boys grow up. I can’t see a landlord being very happy about that.

Billy,

I’ll do it over the weekend, but you are right on the way that superficial comparisons are pretty standard.

Your last point is why buying makes sense. Owning something is different than leasing. Owning over the long term is generally a benefit even economically, it is just less so than people think, and for different reasons. The current environment has exposed those folly’s, inflation over time tends to obscure them.

With both our house purchases, my wife and I have purchased below where we could based on our salaries. In fact, our last house we could have afforded on one of our salaries (plus the usual bills.) We went through a couple of realtors who kept showing us $150-$250K houses for our first home. On paper, we could have afforded it, barely. That was 13 years ago, and it was a LOT of house. But, since both of us had been laid off in the past, we didn’t want to assume that much risk.

We settled for an $89K house, which we maintained and did very few upgrades on. We ended up with a good chunk of change for our current house. On this house, we did an 80/10 mortgage, with cash left over for some necessary upgrades, and a few extras (like all new S/S appliances.) We’re also building my 36×40 workshop/garage almost completely with cash.

It all comes down to making responsible choices about the risks you’re willing to assume.

We moved to our current house so we’d have room to have a big garage, a big garden, a place for goats and chickens, apple trees, and room to raise a family. How much is that dream worth?

Oh, and what kind of price do you put on being able to walk out your back door, and put a bullet through a book. No neighbors complaining. No sheriff showing up.

Exactly. That is the most important worth of a house. Same with my wife and I. We love our house, bought it at what looks like the top of the market here in baton Rouge, and I don’t regret it a bit. However, we assume we will stay in it a long time and are fine of we accumulate no equity beyond our payments against the mortgage. Heck, even with a decline we are fine, we just would rather the price at least match inflation.